- The government has removed foreign ownership restrictions on geothermal projects and stopped accepting applications for coal-fired power plants.

- While the shift is nominally driven by environmental goals, corporate developments around the gas sector could be a key driver.

- A recent decision to allow exploration in the South China Sea could be tied to these policy changes.

Over the past three weeks, the government has announced that it is:

- Formally raising the allowed level of foreign ownership from 40% to 100% in geothermal projects with an initial investment of USD 50mn.

- No longer accepting new applications for coal-fired power plants.

- Ending a six-year ban on exploration in disputed waters in the South China Sea.

Energy Secretary Alfonso Cusi announced the formal policy change on geothermal energy this week, as contained in the order he signed last 20 October on the selection process for new renewable projects. The coal policy was announced in an online conference on 27 October. He now describes the government’s goal as “transitioning from fossil fuel-based technology utilization to cleaner energy sources to ensure more sustainable growth.” This is a perceptible shift in policy; for years, Cusi had described the country’s energy mix goals as being “agnostic” on the type of fuel and technology. As recently as last September, he was against a coal ban.

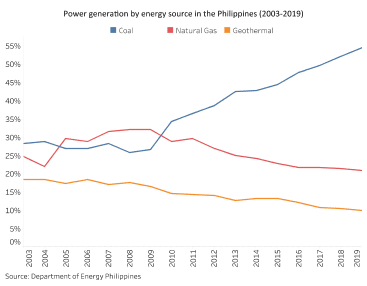

In terms of geothermal energy, the Philippines is the third-largest generator globally. However, its share in the country’s total energy output had been halved to about 10% in 2019 from 20% in 2000. Coal, meanwhile, has doubled its share to 55%. Much of the existing geothermal capacity had been developed from the 1970s to the 1990s by state-owned enterprises, in partnership with Chevron, CalEnergy/Ormat and Marubeni. The government and the foreign shareholders in these plants have sold off their shares over the past decade to locally owned conglomerates such as Energy Development Corporation and Aboitiz Power.

New capacity development in the geothermal sector slowed significantly at the start of the 2000s, for several reasons. First was the privatization of the state power company and the oversupply in electricity generation capacity. Second, green field geothermal development also carried higher risks compared to other types of power plants because of the drilling costs and more cumbersome permitting process. And even though the government passed a renewable energy law in 2008 that provided additional fiscal and non-fiscal incentives, geothermal does not benefit from feed-in-tariffs, unlike other renewables, which have, therefore, grown faster than geothermal.

The Department of Energy estimates that the country’s geothermal reserves to be approximately 4,000 megawatts, compared to the current installed capacity of 1,900 mw. By removing the cap on foreign ownership, foreign firms may be able to manage their risks better, as well as raise capital for local development. Nonetheless, given the sector’s headwinds, foreign investor uptake will likely be gradual at best.

But gas is the real story

The prohibition on new coal-fired power plants will cause base load power development to shift to gas. Nuclear remains a very heavy lift. Given how the energy department has pivoted on the topic, the policy shift may have been driven by an alignment of interests between three key players: Dennis Uy, a businessperson strongly associated with President Rodrigo Duterte; China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC) and; Manuel Pangilinan of First Pacific, the holding company of Indonesia's Salim family. All three could become key players in the gas sector.

In mid-October, Duterte lifted a six-year ban on exploration in the South China Sea. The Chinese response was tepid, even encouraging, indicating that the move had been communicated to Beijing beforehand. The Philippine government emphasized that any activity in the area would have to be consistent with the November 2018 memorandum of understanding on joint exploration and cooperation with China.

The first piece of the puzzle is Pangilinan, whose First Pacific has the controlling interest in two key exploration areas in the South China Sea: Reed/Recto Bank through the UK-listed Forum Energy, and northwestern Palawan through PXP Energy Group. Since 2013, Forum Energy had been in discussions with CNOOC on joint exploration and last week Forum said negotiations were taking place between one of its subsidiaries and CNOOC. Pangilinan and First Pacific are not exactly aligned with Duterte. Their telecommunications firm Smart/PLDT and local water utility Maynilad have been the targets of Duterte’s ire. He has ordered the renegotiation of Maynilad's service contract and often criticizes the telco for its service, using it as justification for the entry of a third player. So, Pangilinan and CNOOC alone are unlikely to have enough leverage for a major policy shift.

The second and key piece could be Uy; some local media and government critics describe Uy as Duterte’s top crony, based on the expansion of his business from petroleum retailing previously to telecommunications, casinos, property development, convenience stores, and restaurants within the last four years. Uy calls Duterte a mentor. In partnership with China Telecom, he is launching the country's third telco based on a license granted during Duterte's term.

In 2018, one of Uy’s companies signed a deal with CNOOC to develop an LNG terminal in the Philippines. The project stalled in 2019. However, Uy’s plans also include the construction of a 2,000-mw gas-fired plant, likely with CNOOC as the technology partner. Instead of the LNG terminal, Uy turned his attention in late 2019 to acquiring Chevron’s 45% stake in the Malampaya gas field, which supplies five power plants totaling 3,200 megawatts on the main island of Luzon. Shell, which had discovered the field and is its operator, this summer announced its plan to sell its 45% share, and the rumored bidders include Uy, Pangilinan and San Miguel Corporation (which was planning to build about 3200 mw of coal until the policy change). Shell’s contract ends in 2024, and its estimate based on current data is that the field can produce until 2027.

Should Pangilinan’s Forum Energy be successful in Reed Bank, it can connect to Malampaya’s pipeline to supply the existing gas-fired plants concentrated in the province of Batangas. And with coal-fired power plants no longer being licensed, Uy will have a future role in the energy sector, potentially as the supplier of gas, whether from Malampaya or Forum, or through an LNG terminal, and possibly also setting up his own power plant. Uy is under pressure to cement these relationships because if the opposition wins in 2022, then his business deals could be targeted.