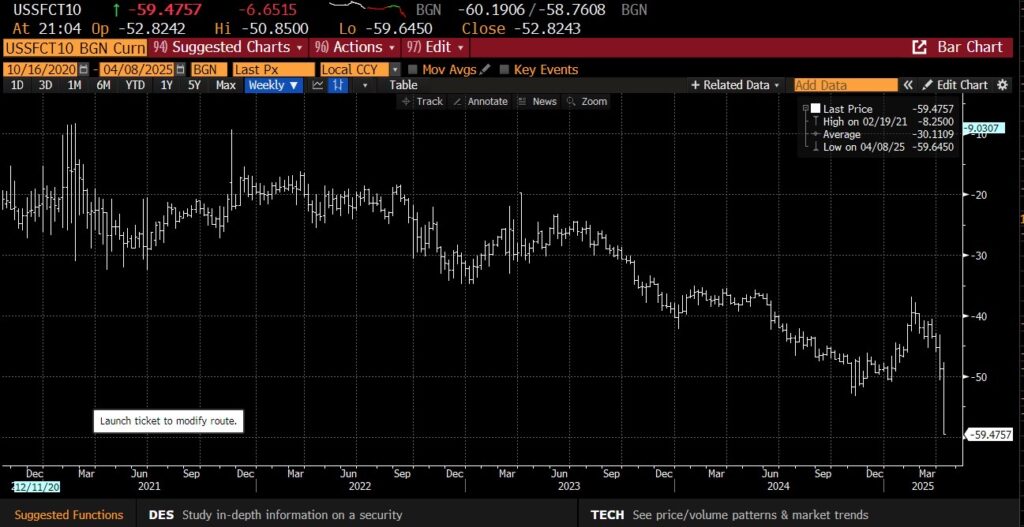

Speevr Intelligence

The Speevr Intelligence daily updates provide in-depth alternative perspectives on key themes and narratives driving financial markets. Our unique collection brings Speevr's exclusive content together with partners' research and analysis.