While the United States and China have not gone as far as re-introducing or increasing tariffs on each others’ imports, the war of words between the two trading superpowers has clearly escalated with Hong Kong caught in the middle.

In line with our expectations the Chinese Renminbi has depreciated versus (a weaker) Dollar and in nominal effective exchange rate terms in recent weeks (see Figures 1 & 2).

Precedent suggests the Renminbi’s slide to an 11-week low is not coincidental but the by-product of the PBoC’s conscious decision to modestly weaken its currency and send a clear, if subtle message to the United States that China can retaliate in more ways than one.

The implications of a breakdown in US-China relations and a resumption of a full-blown trade war would of course reach far beyond a possible acceleration in the pace of Renminbi depreciation.

For starters any sustained Renminbi weakness would likely increase the odds of other Asian currencies also depreciating versus the Dollar with hands-on central banks keen to maintain their countries’ export competitiveness, particularly at this current juncture.

It is no coincidence, in our view, that Asian currencies on the whole remain highly correlated with the Renminbi and have underperformed since 7th May (see Figures 3 & 4).

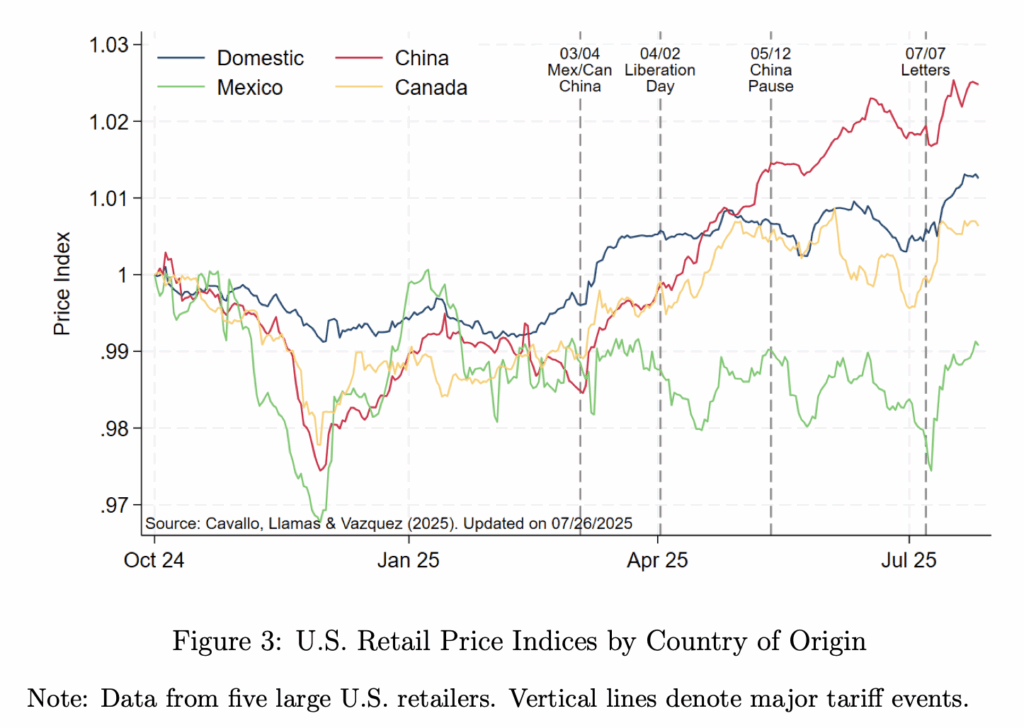

Moreover, the introduction of new import tariffs would, based on precedent, likely have a material and negative impact on world trade at a time when macro data suggest that global economic activity has only just started to very slowly recover from a very low base.

Any further headwind to global trade would likely delay any meaningful recovery in global supply and demand (see Figure 5) and cast further doubts on whether sequential global GDP growth can forge a V-shaped recovery in Q3 and Q4 2020 – the topic of our next Fixed Income Research & Macro Strategy report.

Renminbi’s slow slide in the context of deteriorating relations with US speaks volumes

In Conservative FX Markets Testing (Some) Extremes (7th May 2020) we warned that based on precedent a resumption of the trade war with the United States would likely result in Chinese policy-makers retaliating by weakening the Renminbi. Seemingly the thinking from China’s side in the past 18 months has been that a weaker Renminbi serves as a warning to the United States that China can retaliate in more ways than one. It also makes Chinese exports more competitive, which can at least partly compensate for any downturn in exports triggered by United States import tariffs.

It is indeed important to remember that the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) fixes the daily USD/CNY central parity rate around which spot can trade 2% either side. If USD/CNY spot hits either the strong or weak end of the band the PBoC has to intervene in the FX market (buying or selling Dollars). So the PBoC in effect dictates the Renminbi’s direction, taking into consideration the broader economic costs and benefits of an appreciating or depreciating currency in the context of underlying demand for the Renminbi and thus China’s balance of payment flows[1]. The United States of course does not have this ability to control its currency, with the Dollar’s weakness or strength largely the by-product of market forces – arguably a great source of frustration for US President Trump who has regularly advocated a weaker Dollar.

While the United States and China have not gone as far as re-introducing or increasing tariffs on each others’ imports, the war of words has clearly escalated with Hong Kong caught in the middle.

The Chinese National Congress pm 28th May approved the proposal to impose a new national security law on Hong Kong, paving the way for the law to be finalized in coming months. US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo told the US Congress on 27th May that the US administration no longer views Hong Kong as an autonomous Chinese region. President Trump, who is due to hold a news conference about China on 29th May, has a number of options at his disposal. He hinted this week at possible sanctions against China and could issue an executive order removing some or all of Hong Kong's special status under US law.

In such a scenario China could retaliate against US companies by placing them on an “unreliable entity list” to restrict trade or by throwing up other obstacles. Similar tits-for-tats in 2018 and 2019 arguably led to a full-blown trade war between two trading giants which extended well beyond the import/export of goods.

Given this backdrop it is perhaps no surprise, in our view, that since 7th May the PBoC has fixed USD/CNY 0.5% higher (i.e. fixed the Renminbi weaker) – see Figure 1 – and allowed the Renminbi to depreciate 0.9% versus a weakening Dollar (see Figure 2). As a result the Renminbi Nominal Effective Exchange Rate (NEER) has depreciated 2.3% to an 11-week-low according to our estimates (see Figure 1). In comparison the Renminbi (and the Dollar) had been range-bound between end-March and early May.

So while the Renminbi’s depreciation has so far been modest in the greater scheme of things, it does suggest in our view that Chinese policy-makers are sending the United States a clear, even if still subtle message that in the event of a full-blown trade war they can once again retaliate in more ways than one.

Implications of full-blown US-China trade war would reach far beyond Renminbi

The implications of a resumption of a full-blown trade war between the United States and China would of course reach far beyond a possible acceleration in the pace of Renminbi depreciation.

For starters any sustained weakness in the Renminbi would likely increase the odds of other Asian currencies also depreciating versus the Dollar, in our view, with hands-on domestic central banks keen to maintain their countries’ export competitiveness vis-à-vis China, particularly at this current economic juncture. The correlation between daily percentage changes in the Renminbi and daily percentages changes in Asia-Pacific currencies indeed remains reasonably high (see Figure 3) and it is no coincidence in our view that Asian currencies have on the whole underperformed in the past three weeks (see Figure 4).

Given that the economies of Australia, and to a lesser extent New Zealand, are also closely tied to China’s the first instinct would be to expect Renminbi weakness to eventually feed through to the Australian and Kiwi Dollars. However, these two currencies are largely the by-product of market forces, with the Reserve Bank of Australia and Reserve Bank of New Zealand more hands-off than their Asian counterparts in our view. Therefore Renminbi weakness may not translate to weaker Australian and Kiwi Dollars and indeed since 7th May these antipodean currencies have outperformed (see Figure 4).

Moreover, the introduction of new import tariffs would, based on precedent, likely have a material and negative impact on world trade at a time when macro data suggest that global economic activity has only just started to very slowly recover from a very low base. Figure 4 shows that historically global GDP and trade growth have gone hand in hand. Global trade growth slowed materially between Q3 2018 and Q4 2019 – and was negative in quarter-on-quarter terms in four of those five quarters – which we attribute in large part to the introduction of widespread tariffs on US, Chinese, European Union and other major trading nations’ imports in 2018 and 2019.

The volume of global trade contracted about 2.8% qoq in Q1 2020 while we estimate that global GDP retracted about 4.5% qoq – both the largest contractions since Q1 2009 (see Lessons Learnt from Q1 Collapse in Global GDP, 21st May 2020). The consensus forecast, which we share is that global trade and GDP growth contracted at even greater rates in Q2. Any further headwind to global trade would likely delay any meaningful recovery in global supply and demand and cast further doubts on whether sequential global GDP growth can forge a V-shaped recovery in Q3 and Q4 2020 – the topic of our next Fixed Income Research & Macro Strategy report.

[1] For example if the market is a net-seller of Renminbi (and the currency under depreciation pressure) the PBoC has to sell Dollars (FX reserves) in order to stop the Renminbi from weakening. Conversely, if market demand for the Renminbi is strong, the PBoC has to buy Dollars (and sell Renminbi) to stop the currency from appreciating, which may in turn contribute to domestic inflationary pressures.