The Korean Won Nominal Effective Exchange Rate has appreciated 4.7% since the 41-month low recorded on 12th August to a six-month high, with the Won up against the currencies of Korea’s largest trading partners, namely the Yen, Euro, Renminbi and Dollar.

A common view is that, with China accounting for about a third of Korea’s total trade, day-to-day speculative flows searching for a proxy to USD/CNY drive the Won. However, in the past 11 weeks USD/KRW has fallen 4.6% whereas USD/CNY has been broadly unchanged, suggesting that other balance of payment flows are driving the Won.

Foreign portfolio inflows into Korean equities and bonds have in recent years often closely correlated with USD/KRW. However, this correlation broke down between mid-March and early October and the Won NEER has been far more stable than volatile portfolio inflows into Korea, trading in a 9.5% range since March 2016.

We see a number of explanations for these dislocations, including the FX-hedging of local-currency bond purchases. Moreover, historically sizeable Korean trade and current account surpluses, which have shrunk sharply in the past 12 months on the back of slowing trade with China, have had a material impact on the Won’s medium-term trend.

However, in the past 108 months, the average Won NEER has rarely appreciated or depreciated by more than 2-3% mom (see Figure 13). Moreover, these moves have tallied with changes in the (adjusted) $-value of the Bank of Korea’s FX reserves, suggesting that the BoK intervenes in the FX market to smooth the Won NEER.

The BoK is probably not overly concerned with (modest) intra-day or even monthly moves in USD/KRW and its FX intervention has been light-handed, particularly in recent years. But it has shown a willingness to keep the Won NEER in a narrower band than if left to its own devices, with a bias towards selling Won/buying Dollars.

With the Won having made sizeable gains in recent months, BoK interest rate policy tight relative to CPI-inflation, GDP growth volatile and the outlook for US-China trade still murky despite recent developments, we expect the BoK to cut rates further and at the very least slow any Won appreciation in coming months to maintain currency competitiveness.

Won Nominal Effective Exchange Rate up 4.7% to six-month high

The Korean Won Nominal Effective Exchange Rate (NEER) has appreciated 4.7% since the 41-month low recorded on 12th August to a six-month high, with the Won up 4.6% against the US Dollar according to our estimates (see Figure 1).

The Won has appreciated against all the currencies of Korea’s main trading partners, with the exception of Sterling which rallied sharply in the wake of the UK and EU on 17th October agreeing to a new Brexit deal and the South African Rand (see Figure 2). Notably, the Won’s largest gains since 12th August have mainly been against the currencies of Korea’s largest trading partners, namely the Japanese Yen, Euro, Chinese Renminbi and US Dollar. As a result these four currencies’ depreciation has accounted for about 4.2 percentage points of the Won NEER’s 4.7% gain in the past 11 weeks.

This begs the question of whether this is simply a short-term Won recovery from depressed levels or the beginning of a longer-term uptrend. To answer this question we need to understand the relative importance of balance of payment flows (current account balance, portfolio flows and other capital flows) in driving the Won and the Bank of Korea’s reaction function to moves in its currency.

Speculative flows treating USD/KRW as proxy for USD/CNY

A common view is that the Won is simply a proxy for the Chinese Renminbi and therefore that USD/KRW tends to trade in line with USD/CNY. This intuitively makes some sense given that China is Korea’s largest trading partner, accounting for about a third of its total trade, and Figure 3 indeed shows that most of the time the USD/KRW and USD/CNY crosses are closely correlated.

The underlying rational is that Renminbi weakness is typically associated with Chinese economic stress, which dents Korea’s trade surplus with China (given strong trade linkages between the two economies) and other economies reliant on Chinese trade, and Korea’s GDP growth, which in turn deters speculative (or “hot-money”) inflows into Korea – the net result being balance of payments pressure on the Won. Moreover, if the Renminbi (and the currencies of Korea’s other main trading partners) is weakening, the Bank of Korea is more likely to be inclined to allow the Won to depreciate in order to maintain export competitiveness.

However, Figure 3 also points to a number of episodes in the past two-and-a-half years when the correlation between USD/KRW and USD/CNY has broken down and inverted (highlighted in grey). For example, since 12th August the Won has appreciated 4.6% versus the Dollar whereas the onshore Renminbi has been broadly unchanged – resulting in the 4.6% appreciation in the Won versus the Renminbi (see Figure 2).

These episodic breakdowns in correlation are also evident when we look at the Won and Renminbi NEERs (see grey highlights in Figure 4) and suggest to us that balance of payment flows other than speculative flows at times drive the Won.

Won NEER more stable than volatile foreign portfolio inflows into Korea

Foreign portfolio inflows into Korea – foreigners’ net purchases of Korean equities and local-currency bonds – are typically very volatile (see Figure 5). In recent years, they have often closely correlated with USD/KRW, with large net inflows/outflows associated with material moves lower/higher in USD/KRW. Five months ago we were bullish the Won, pointing to the “recent acceleration in foreign purchases of domestic bonds”, and in the following month the Won was the second best performing Asian currency (after the Thai Baht), appreciating 2.7% versus Dollar (see More to FX markets than US-China trade war, 24 May 2019).

However, we can also pinpoint numerous episodes when this correlation has broken down. For example, between 20th March and early October, net foreign portfolio inflows into Korea amounted to about $33.1bn and yet the Won weakened about 7% versus the US Dollar (see Figure 5).

The correlation between foreign portfolio inflows and the Won NEER is even les clear-cut (see Figure 6), which is perhaps unsurprising given that the US Dollar accounts for only about 14% of the Won NEER (see Figure 2). Specifically, the Won NEER has been far more stable than volatile foreign portfolio inflows into Korea, trading in a 9.5% range since March 2016.

We see two explanations for this dislocation in the correlation between foreign portfolio flows into Korea and the Won’s performance.

First, the bulk of foreigners’ net purchases of Korean bonds – which amounted to $34.1bn between mid-March and early October (see Figure 7) – were currency-hedged and thus had only a modest impact on USD/KRW (foreigners’ bond purchases show up as an FX inflow in the portfolio flows component of the balance of payments but the offsetting sale of Won/purchase of Dollars in the FX market shows up as an FX outflow in the “other investment” component of the financial account). Note that between mid-March and early October, there were net foreign equity outflows of about $1bn.

Second, large balance of payment flows other than foreign portfolio and speculative flows – such as the trade and current account balances – have had a material impact on the Won’s medium-term trend, in our view.

US-China trade war has weighed on Korea’s trade and current account surpluses

Korea’s quarterly current account surplus, seasonally-adjusted, has shrunk considerably in the past 12 months from about $25bn to about $15bn according to the Bank of Korea (see Figure 8).

During that period the quarterly trade surplus on goods has halved from a record-high of $34bn in Q3 2018[1], with the $10.5bn collapse in Korea’ s trade surplus with China accounting for about 60% (see Figure 9). Korea’s quarterly trade deficit on services has shrunk by about $2bn and the primary income surplus has risen by about $5bn.

The sharp narrowing of Korea’s total goods trade surplus has been due to the contraction in the $-value of exports (-12% year-on-year in the 3-months to August) outweighing the contraction in imports (4.5% yoy), as per Figure 11. In particular, the $-value of Korea’s merchandise exports to China fell by over 20% yoy in June-August whereas Korea’s imports from China were up 4.4% yoy (see Figure 10). The timing of this collapse in Korea’s exports to China corresponds to the escalation in the trade between the US and China and the sharp slowdown in China’s overall trade.

Figure 12 points to a positive historical relationship between Korea’s historically sizeable merchandise trade surplus and the Won NEER. Specifically, the halving of Korea’s quarterly trade surplus in 12 months to August to about $17bn seemingly contributed to the Won NEER’s 7% depreciation over that period.

So while the ebbs and flows in speculative flows tracking USD/CNY and foreign portfolio inflows into Korea often dictate where USD/KRW spot trades day-to-day, the Korean trade surplus has a strong bearing on the Won NEER month-in, month out – which in itself is perhaps unsurprising.

However, what also stands out from Figure 12 is that the monthly average of the Won NEER has typically trended within narrow corridors. In the past nine years or 108 months it has rarely appreciated by more than 3% mom or depreciated by more than 2% mom (see Figure 13). Actually, the average Won NEER has appreciated by more than 3% mom only twice – in September 2013 (+3.1%) and October 2015 (+3.2%) – and depreciated by more than 2% only seven times (weakening on average by 2.4% mom in these seven months).

Bank of Korea – light FX intervention to smooth Won NEER

Moreover, these modest monthly changes in the Won NEER tally with changes in the Bank of Korea’s FX reserves (see Figure 13). Specifically, in months when the Won has appreciated, central bank FX reserves (adjusted for underlying FX-valuation effects) have tended to rise – suggesting that the Bank of Korea was selling Won, buying FX. Conversely, in months when the Won NEER has depreciated, central bank FX reserves have tended to fall – suggesting that the Bank of Korea was buying Won, selling FX. This pattern is even clearer if we look at the 3-month moving average in the percentage change in the Won NEER and Bank of Korea FX reserves (see Figure 14).

This suggests to us that the Bank of Korea intervenes in the FX market to smooth monthly moves in the Won NEER.

To be clear, we do not think that the Bank of Korea is overly concerned with (modest) intra-day moves in USD/KRW spot generated by volatile speculative and foreign portfolio inflows or even with monthly moves in USD/KRW. Indeed Figure 15 points to a more limited correlation between monthly changes in the average USD/KRW exchange rate and monthly changes in the Bank of Korea’s FX reserves, particularly in the past 3-4 years.

Intuitively this makes sense to the extent that the US accounts for only 14% of Korea’s total trade and the Won accounts for only 14% of the Won NEER. Put differently, we think the Bank of Korea is focussing on the Won NEER to the extent that it has a far greater impact (than simply USD/KRW) on Korea’s overall trade competitiveness and economy. In the same way, the People’s Bank of China focuses on the Renminbi NEER rather than on USD/CNY per se (or other currency crosses for that matter), at least from a monetary policy perspective (the PBoC has arguably used USD/CNY as a “weapon” to retaliate against the US in the ongoing trade war – see Renminbi devaluation “lite”: Tool and weapon, 29 June 2018, and Renminbi depreciation – Case of déjà vu, 16 May 2019).

Not only is the Bank of Korea reasonably comfortable with daily or even monthly moves in USD/KRW, in our view, it has also allowed underlying balance of payment flows to guide the Won NEER’s general medium-term direction and FX intervention has been light, with the FX-valuation adjusted $-value of its reserves rarely rising or falling by more than 1% per month (see Figure 13). If anything, Bank of Korea FX intervention has been even lighter-handed in recent years, with the monthly percentage changes in FX reserves moderating (see Figure 17).

Specifically, the Bank of Korea allowed a rising trade surplus and large foreign portfolio inflows to drive the Won higher between end-2011 and April 2015 and between March 2016 and end-2018 (see Figures 12 & 13). In September and October, the average Won NEER has appreciated by respectively 1.7% and 0.7%. Similarly, the Bank of Korea allowed the Won to weaken between end-2018 and summer 2019 in the face of a narrowing trade surplus and growing concerns about domestic, regional and global trade and GDP growth (the blue line in Figure 13 was more often in negative than positive territory).

Having said all of that, the Bank of Korea has shown a willingness and ability to fade monthly changes in the Won NEER, effectively keeping it a narrower band than if the Won was left to its own devices. The mostly positive monthly changes in its FX reserves (see Figures 13-15) and upward trend in the $-value of its FX reserves (see Figure 16) in the past decade years suggest that the Bank of Korea has more often faded Won appreciation (selling Won, buying Dollars) in a bid to enhance export competitiveness than it has faded Won depreciation.

Bank of Korea’s willingness to fade Won conditioned by numerous variables

The Bank of Korea’s willingness to control and cap the monthly pace at which the Won NEER gains or loses competitiveness and impacts imported-inflation is likely conditioned by a number of variables, including:

i) The ebbs and flows in capital migrations attracted or dispelled by Won valuations (see Asian currencies keeping their head in a world losing its own, 26 May 2017);

ii) The underlying trend and seasonal patterns in trade and current account surpluses;

iii) Developments in the US-China trade war (see Trading Places, 6 April 2018) and their impact on global trade and economic growth and on the currencies of Korea’s major trading partners, including the Chinese Renminbi;

iv) Volatile Korean economic growth; and

v) Consumer price inflation and the real policy rate;

Korean GDP growth and inflation probably do not justify a materially stronger Won

Korea’s quarterly GDP growth remains volatile, having oscillated between -0.4% qoq and +1.0% qoq year-to-date (see Figure 18).

Moreover, inflationary pressures have continued to weaken, with headline CPI-inflation turning negative in September (-0.4% yoy) for the first time in decades and core CPI-inflation (+0.5% yoy) down to a 20-year low (see Figure 19).

As a result, the Bank of Korea’s “real” policy rate remains high by historical standards, despite the central bank’s 25bp rate cuts in July and October, and we see a strong possibility of the Bank of Korea cutting rates again in coming months (see Figure 20). The nominal policy rate deflated by headline CPI-inflation stood at 1.9% in September – a 12-year high – while the nominal policy rate deflated by core CPI-inflation stood at 1.0% yoy, the top end of a -1.2/+1.2% yoy range in place since mid-2013.

All other things equal, a high real policy rate is likely to act a brake on Korea’s GDP growth and inflation and incentivise the Bank of Korea to fade Won appreciation, in our view.

Bank of Korea likely to maintain steady hand on Won’s progress

With the Won having made sizeable gains in recent months, Bank of Korea interest rate policy still tight relative to CPI-inflation, GDP growth volatile and the outlook for US-China trade murky despite recent positive developments, we would expect the Bank of Korea to at the very least slow the pace of any further Won appreciation in coming months in a bid to maintain currency competitiveness.

There is a risk that US President Trump, who has repeatedly criticised China and Germany for having under-valued currencies, turns his attention to the Korean Won. However, we would note that i) Korea accounts for only 3.5% of US merchandise trade; ii) the Won appreciated in 2012-2018 and only recently weakened, iii) Bank of Korea FX’s intervention has been light-handed, with only a gradual build-up of FX reserves and iv) South Korea remains a key partner for President Trump in his (admittedly sporadic) dealings with North Korea’s leader Kim Jong-un.

[1] Note that trade data from the Bank of Korea differ from those by the Ministry of trade due to measurement differences.

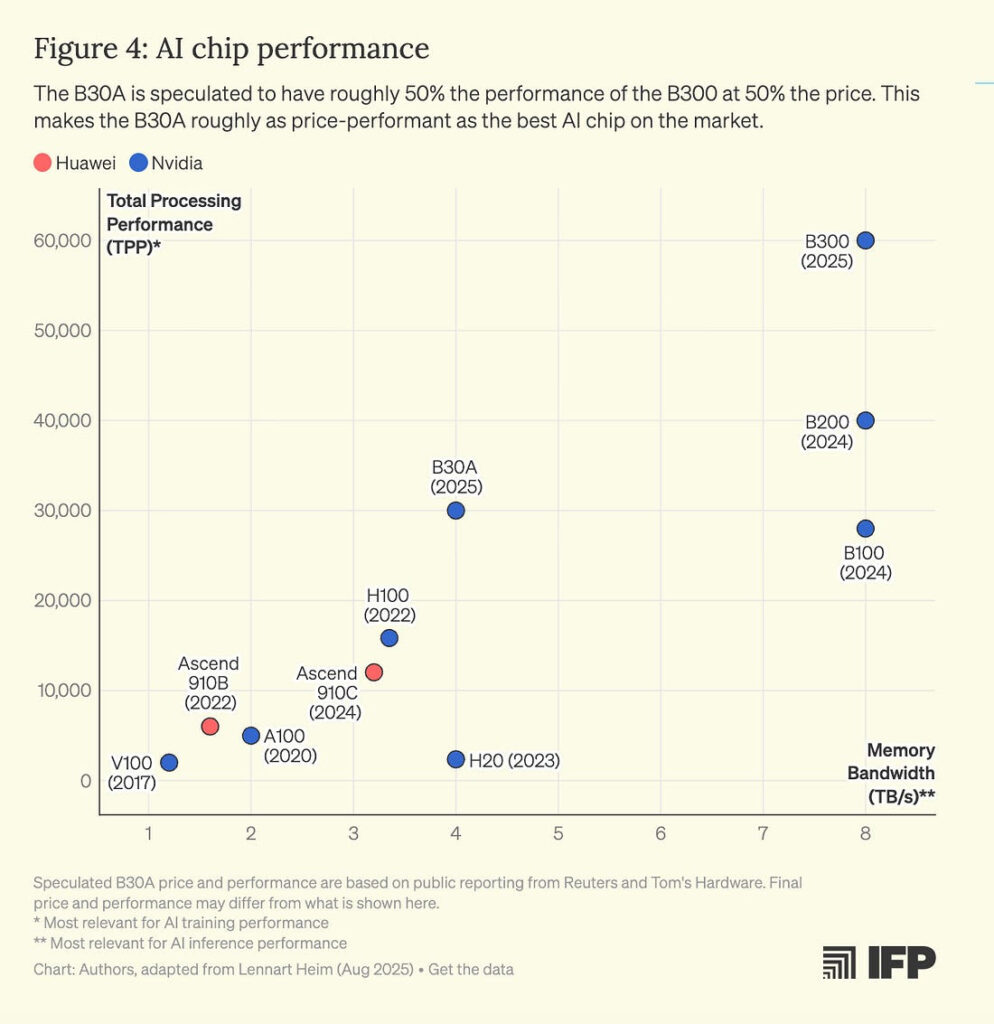

Identifying the Opportunities of The AI Buildout (Part 1)