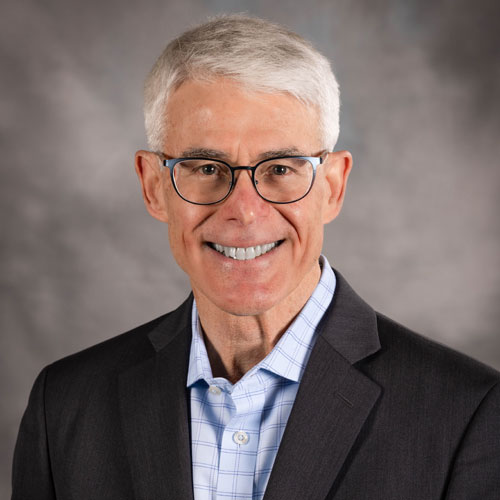

This update summarizes a discussion between Professor Darrell Duffie (Stanford) and the Bloomberg Intelligence team on U.S. bank reserves and adjacent topics. Although the podcast interview is from mid-January 2026, its content remains timely and highly relevant.

Background and Road Map

The discussion also provides a useful backdrop for resuming our coverage of central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) and stablecoins—both key areas of Duffie’s current research, alongside his work on U.S. Treasury markets.

We frame this within a structure first outlined in 2020:

USA Inc. = Big Tech + Fed + Treasury

The AI boom and the increasingly cosy relationship between Big Tech and the U.S. government make this schema far easier to explain today—arguably approaching de facto policy under the Trump administration.

Previously, we noted that the missing piece needed to complete this framework was the introduction of either a CBDC or a government-sponsored stablecoin. We left the discussion leaning slightly toward the latter, given privacy concerns, potential risks to the existing fractional-reserve banking system, and the possibility that a stablecoin structure or tokenization could help alleviate recurring dysfunction in Treasury markets.

As the largest foreign holders of U.S. Treasuries, Japanese investors play a pivotal role in sustaining the ecosystem described above. On that front, we are fortunate to have one of the world’s most perceptive Japan observers, Tobias Harris at Japan Foresight, keeping us informed.

Ample Reserves and Fed Stigma with Darrell Duffie

Full interview: Macro Matters: Ample Reserves and Fed Stigma with Darrell Duffie. The total runtime, including introductions, is approximately 26 minutes. If you have the time, it’s well worth listening to the full episode before reading our summary below.

Darrell is invariably thoughtful and precise in his words, with views grounded in rigorous primary research and informed by market practitioners.

For additional work and publications by Duffie, see: https://www.darrellduffie.com

Topics: Federal Reserve market operations, regulatory “red lines” for banks, and the role of reserves within the U.S. payments system.

Introduction: The Academic Perspective on Market Plumbing

The conversation begins by establishing the expertise of Darrell Duffie, a Stanford professor whose career has evolved from studying the math of interest rates to the design of bond markets and financial regulation. He frames the current environment as a critical intersection where regulatory issues and market liquidity meet, necessitating a deep investigation into how the Federal Reserve manages the “plumbing” of the financial system.

Fed Independence and Political Pressure

Addressing the recent subpoena of Jerome Powell, Duffie argues that the Federal Reserve’s independence is not just a structural formality but a critical economic pillar.

- The “Gold/Dollar” Signal: Duffie notes that while bond yields (long-term rates) were relatively quiet, the movement in gold and the U.S. dollar indicates that the market is pricing in a non-trivial risk.

- The Warning: He asserts that high-quality monetary policy is entirely dependent on this independence and warns market participants not to take it for granted, as it is currently in a state that “bears watching.”

The Implementation Gap: Rates vs. Balance Sheet

Duffie introduces a fundamental distinction: the Fed can announce a rate change (Rates Policy), but it cannot make that rate “stick” without the correct amount of liquidity (Balance Sheet Policy).

- The Liability Focus: He argues that while most focus on what assets the Fed buys (Treasuries/MBS), the real “action” and market consternation are on the liability side—specifically, the quantity of reserves held by banks.

- Transition to “Bills-Only”: Duffie nuances the Fed’s future asset strategy. He expects a gradual exit from mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and a reduction in long-term Treasuries until they only cover the value of paper currency in circulation. The rest of the balance sheet will likely shift toward short-term Treasury bills to minimize interference in the long-term bond market.

The End of the “Lean” Balance Sheet (Why 2007 is Irrelevant)

Ira Jersey asks why the Fed cannot return to the pre-2007 “scarce reserve” regime, where banks held only a few billion in reserves. Duffie explains that this is structurally impossible due to two modern regulations:

- Regulation YY: Mandates that banks must manage intraday liquidity on their own, proving they do not need the Fed's help.

- RLAP (Resolution Liquidity Adequacy and Positioning): Requires banks to have enough liquidity to survive a total wind-down scenario without assistance.

- The “Red Line”: Duffie cites Jamie Dimon’s experience in 2019, explaining that even if lending money in the repo market is highly profitable, banks will refuse to do it if it means their reserves drop below a regulatory “red line.” This makes the banking system a “reserve hog” compared to the past.

The Payment System: The Fedwire Mechanism

Duffie provides a detailed look at Fedwire, the primary system for large-value payments.

- The Multiplier Effect: Large banks often pay out 5 to 10 times the amount of reserves they actually hold at the start of the day. They rely on “incoming” payments to fund “outgoing” ones.

- Throttling: When reserves are tight, banks engage in “throttling”—intentionally delaying their payments to wait for cash to arrive. This creates a “liquidity crunch” as the entire system slows down.

- The 250-Minute Variation: His research shows that the timing of these payments can shift by over four hours (250 minutes) depending on how “ample” reserves are. The 2019 repo spike was, in fact, signaled by record-late payment timings.

The Failure of the Corridor System and “Stigma”

Will Hoffman asks about the “Corridor System” (the gap between the floor and ceiling of interest rates). Duffie explains why the “ceiling” (the Standing Repo Facility) isn't working:

- ON RRP (The Floor): This facility works well because it allows money funds to park cash at the Fed, preventing rates from falling too low.

- SRF (The Ceiling): The Standing Repo Facility is supposed to prevent rates from spiking. However, it is stigmatized. Banks fear that using it signals to supervisors or the market that they are “weak” or have failed to manage their own liquidity.

- The Canadian Contrast: During a month-end for Canadian banks last fall, repo rates (SOFR) spiked 30–40 basis points above the Fed's intended ceiling because banks were too afraid to use the facility.

The Future: “QE Light” and Reserve Buffers

Duffie clarifies that the current shift—ending Quantitative Tightening (QT) and buying $40 billion in bills a month—is not “Quantitative Easing” in the traditional sense.

- Aggressive Reserve Management: It is a reactive measure to ensure reserves stay above $3 trillion.

- The Shock Test: He notes that because the Fed is supplying so many reserves now, we haven't truly tested if the rebranded Standing Repo Facility has lost its stigma. We likely won't know until a significant market shock occurs.

Conclusion: Auctions vs. Administered Rates

In the final nuance of the discussion, Duffie compares “Standing Facilities” to “Auctions.”

- Why Auctions Work: In an auction (like the 2008 Term Auction Facility), a bank is “winning” a bid, which looks like a profit-seeking trade rather than a plea for help.

- The Fed's Dilemma: The Fed prefers “administered rates” (fixed prices) because it gives them more control over the exact interest rate, but this fixed-price “window” is exactly what creates the stigma. Duffie suggests that moving toward auction-style mechanisms might be the only way to get banks to actually use the liquidity the Fed provides during a crisis.