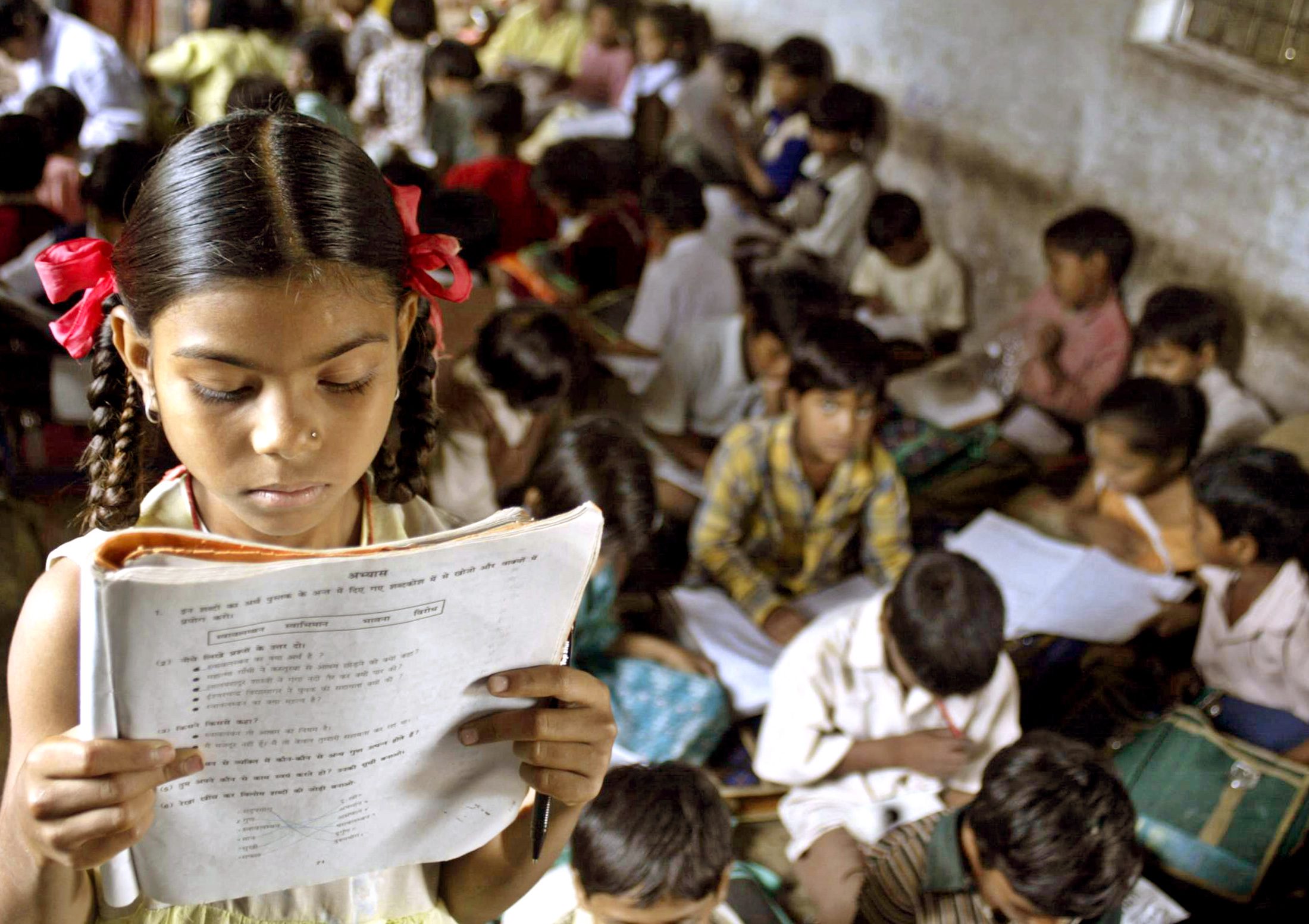

Today there are over 200 registered impact bond transactions globally and 19 transactions in low- and middle-income countries. Over the last decade, impact bonds have gained momentum through repeatedly demonstrating their effectiveness. The very first development impact bond (DIB) on girls’ education generated a more than 60 percent improvement in literacy outcomes in just three years in the Indian NGO Educate Girls’ program, demonstrating the power of simple performance incentives done right. This has grown interest and a community of believers.

These exciting results have unfortunately not led to the anticipated widespread adoption of impact bonds by governments. Since the inception of impact bonds, low- and middle-income country governments have participated as outcome payers in only seven projects globally. Governments have engaged at small scale—motivated by the reputational value of paying for results, the promise of matching donor funds, or the rare politicians’ and bureaucrats’ intrinsic motivation. Impact bonds are narrow innovation instruments, but government adoption is a challenge that also holds true for other simpler results-based financing (RBF) instruments that can be easily integrated in large-scale government delivery.

While impact bonds and RBF may sound complicated or exotic, they are about deploying simple, sensible, and performance-critical delivery management practices.

While impact bonds and RBF may sound complicated or exotic, they are about deploying simple, sensible, and performance-critical delivery management practices: Clarify, articulate, and incentivize target outcomes; provide necessary autonomy to front-line staff; measure progress; reward good performance; and repeat these steps. These practices are routine in high-performing organizations but are often lacking in many developing country governments that manage trillions of dollars of taxpayers’ money.

While we should absolutely debate the mechanics of RBF (financial incentives are not always great, an overemphasis on measurement can sometimes be counterproductive, and so on), we must insist on dramatically accelerating the use of the type of citizen-centered program delivery that the RBF community is pursuing. According to a 2016 Harvard study, only three out of 102 developing countries surveyed are on track to building strong delivery capacity for basic services by the end of the 21st century. The urgent need for progress on critical local issues like inequality and global issues like climate, migration, and global security require us to change course.

Strengthening delivery governance as a precondition

Delivery failures are pervasive and have multiple root causes. However, the few success stories in sustaining excellence in government-led delivery all point to one important precondition: delivery accountability. Citizens must have the information, collective action mechanisms, and power to hold governments accountable to delivery targets—something that the World Bank also argued for in its 2004 World Development Report on service delivery

Rwanda offers a good example. The government has faced strong institutional incentives to deliver for the last 20 years. President Kagame’s government understood that delivering high-quality services to all was critical to its own legitimacy and longevity. That led to significant investments in delivery governance, including transparent yearly reporting of delivery achievements and public evaluations and sanctions of ministers who fail to deliver. In turn, that led to efforts to improve delivery performance through the adoption and scale-up of highly successful RBF programs and the establishment of the famous ”Imihigo” performance contracts, which assign delivery targets and corresponding performance payments to each civil servant. This helps explain Rwanda’s performance in universal health care, which the World Health Organization called “the beacon of universal health coverage” in 2019.

To shift from being a donor-pushed initiative to becoming a government-led practice, the RBF movement needs to deploy and support strategies that scale such delivery governance mechanisms that pressure governments to improve their performance.

Promising strategies for citizens, governments, and donors to prioritize

Today the fields of governance and service delivery work in silos. Governance work has mostly focused on “higher-level” issues like reducing corruption, the free press, and improving procurement transparency rather than governing service delivery, where much of the public spending challenge lies. As a result, most countries do not have independent institutions with the mandate, the resources, and the reach to measure the quality of public programs and hold governments accountable. Often, even ministries of finance do not collect any data to evaluate the quality of services delivered by line ministries, let alone their relevance and impact on citizens. Accelerating delivery excellence in the public sector will require working with existing governance funders and champions to develop stronger governance systems around service delivery.

Strong delivery governance systems will incentivize governments to search for greater impact, lead them to leverage readily available tools like impact bonds and RBF, and ultimately direct taxpayers’ contributions and donor grants to well-functioning delivery systems that actually produce results.

Actors trying to improve governance can create the right macroinstitutional delivery incentives, while the RBF field can equip governments with the practical tools around financing, measurement, and performance management to deliver superior performance.

Strengthening delivery governance will require at least the following investments:

- Increase transparency around delivery targets and delivery performance in key areas of service delivery like education, health, social protection, and the environment. We need governments to establish quality and impact targets and provide regular progress reports for all major policy areas. This would require establishing quality measurement frameworks and investing in measurement teams, data infrastructure, and open data practices that inform citizens of the return on taxpayer money. Affordable and scalable technologies are available to help. Without this building block, citizens will not have the information required to hold governments accountable.

- Strengthen independent institutions that perform quality audits by expanding the mandate and impact monitoring capabilities of national oversight bodies that audit and control governments to independently verify and audit government quality reports, and direct operational improvements where needed. Every ministry could be given a quality rating, for example, which could impact future budget allocations. It would be critical to engage citizens in this process through inclusive social accountability mechanisms to bring the citizens’ voice to life.

- Drive intragovernmental incentives. A third pillar includes the introduction of performance incentives within governments’ various delivery agencies through performance-based grants. For instance, this would apply where ministries of finance make fiscal transfers to other ministries or local government at least partly conditional on delivery performance that is established by quality reports. These intra-governmental performance management measures are critical to reaching the front line of service delivery, and thereby citizens.

Each country will need a contextualized roadmap to achieve strong delivery governance. Donors, citizens, and government champions stand to gain from prioritizing and investing in these systems. They will incentivize governments to search for greater impact, lead them to leverage readily available tools like impact bonds and RBF, and ultimately direct taxpayers’ contributions and donor grants to well-functioning delivery systems that actually produce results.