The explosion of overdraft fees makes basic banking expensive for people living paycheck to paycheck. Banks and credit unions generate over $34 billion in overdraft fees annually by one estimate. What those with money experience as ‘free checking’ is quite expensive for those without. Prior research has focused on who pays overdraft, finding a small number of people (9%) are heavy overdrafters accounting for 80 percent of the fees. Not as carefully researched is whether this is just a small part of banks’ general business model, or whether for some banks overdraft has become their main source of profit. In fact a few small banks have become overdraft giants relying on overdraft fees as their main source of profit. These banks are really check cashers with a charter. Why do bank regulators tolerate this?

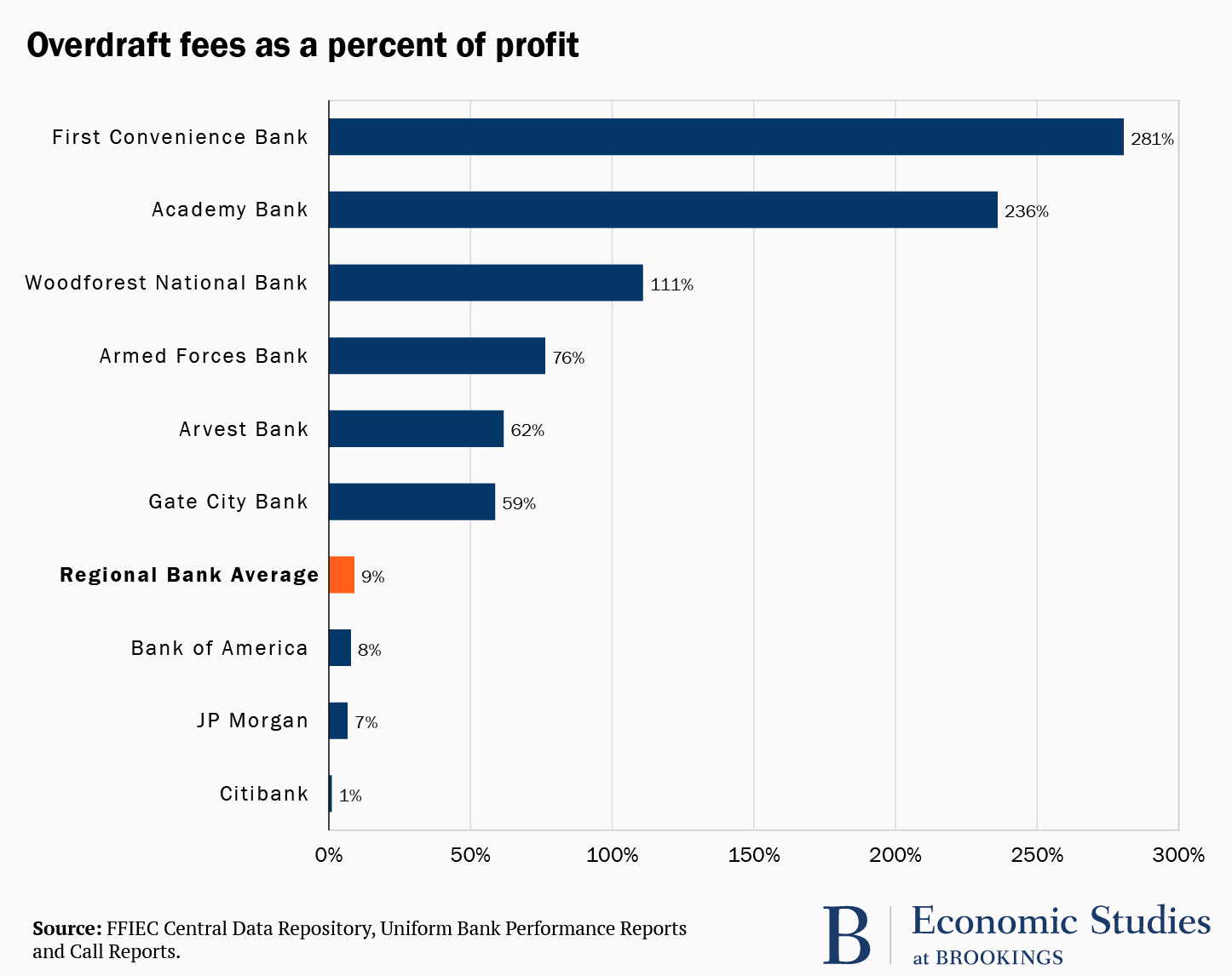

For six banks, overdraft revenues accounted for more than half their net income. Three had overdraft revenues greater than total net income (meaning they lost money on every other aspect of their business). First National Bank of Texas (doing business as First Convenience Bank) made over $100 million in overdraft fees yet posted an annual profit of just $36 million in 2020. Academy Bank and Woodforest National banks likewise made more money on overdraft revenues than profits in 2020. All three were entirely reliant on overdraft fees for any profit in 2019 as well. This is not a one-year blip; it is their business model. Armed Forces Bank, Arvest Bank, and Gate City Bank all rely on overdraft fees for more than half their profit.

Five of these six banks are national banks, regulated by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC). Arvest Bank is a state-chartered institution whose primary federal regulator is the Federal Reserve (Saint Louis District), which seems to tolerate Arvest’s increasing reliance on overdraft as they went from 54 to 62 percent of total profit between 2019 and 2020. These regulators that allow banks to have a business model that depends on a single fee, charged only to consumers who run out of money, are not protecting the ‘safe, sound, and fair operation’ of the banking system.

It is disturbing that regulators tolerate banks that are mostly or entirely dependent on overdraft fees for profitability. Most of these are banks are regulated by the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), but others are primarily federally regulated by the Federal Reserve and the FDIC has backup authority over all insured institutions. From a consumer protection stance, these entities operate more like check cashers and payday lenders than banks. From a safety and soundness proposition, reliance on this one highly costly fee is not sustainable. Don’t take my word for it: Oliver Wyman rang the alarm bell on overdrafts: “What should banks do about overdraft? We believe the crisis is accelerating the need to replace an antiquated product and an unsustainable value exchange.”

These are small banks, and most would be considered very small. Five had between $1 billion and $3 billion in assets (about one-hundredth the size of JPMorgan Chase). However, these banks may not even be the worst overdraft abusers. The smallest banks (those with assets totaling less than $1 billion) and most credit unions are not required to report their overdraft fee revenue at all. Researchers and consumer advocates have no idea how reliant they are on overdrafts. Unless bank regulators are asking these questions, the regulators may not know themselves. Regulators need to collect and publicize overdraft data for all banks and credit unions regardless of size.

Related Content

In principle, overdraft fees are intended to deter depositors from overdrawing their accounts. There is a customer benefit to not having your purchase declined at the cash register. However, overdrafts are incredibly expensive: $35 to cover a $25 purchase that is repaid in two days is equivalent to an annual percentage interest rate (APR) greater than 25 thousand percent. Granted, APR is not always a useful tool to compare products, but it is one most consumers are familiar with, and no actual loan on those terms would ever be permitted. This is why the decision to label overdraft as a fee instead of a loan—even though it is the extension of short-term, small dollar credit—has significant regulatory consequences. And it’s why it could be reversed by future regulators.

In practice, overdrafts are the business model for these six banks and maybe more. These entities are not really banks in the traditional sense of taking deposits, making loans, and helping customers and the economy. They are a combination of payday lenders and check cashers, whose business model depends on a single product with a sky-high annual interest rate that is only paid by people who run out of money.

Bank and credit union regulators need to crack down on these institutions that are operating in a neither safe nor sound manner. They should start by putting any institution for which overdraft is more than 50 percent of their total profit under strict consent decree. If the institution cannot change their business model then their ability to maintain their charter comes into serious question.

Regulators ought to reconsider whether the overdraft product is really a loan, not a fee. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau should also engage. Lending money and then recouping it later, plus something extra, is economically a loan. Calling it a fee may exempt it from certain regulations, but it does not change its nature.

Finally, all banks and credit unions should be required to offer a basic, low-cost, no overdraft fee product. Bank On and the FDIC have both drafted requirements for these types of accounts. The American Bankers Association has called on all banks to offer them. Regulators and Congress should require it. This is a far more effective way to address the problem of the unbanked than other ideas, such as postal banking, because the main reason the unbanked cite for not having an account is cost, not branch location or hours.

Life before and especially during the pandemic forces those on the economic edge to make difficult financial choices with substantial health consequences. Now more than ever banks need to be a source of support for people, not fee generators. Banks reliant on overdrafts for their profits are no more than check cashers with a charter. Regulators are supposed to protect that charter; now, they need to act.